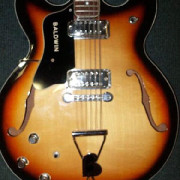

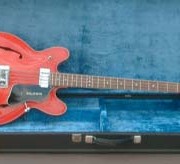

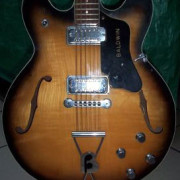

Baldwin 700 series

The old Baldwin Piano and Organ Company of Cincinnati, Ohio, once decided that electric guitars were needed to complement its product range. They choose to acquire in September 1965 the famed builder Burns of London, England, then virtually bankrupt.

‘British Invasion’ music was just raging in USA at that time. Offering guitars with a ‘Made in England’ on sounded like a wise idea. Vox was about to reap a big success in America thanks to its U.K. image.

Unlike the Vox brand, Burns guitars weren’t really associated to the British rock music boom of the mid-60′s. Their main endorsees were The Shadows, who switched from Fender to Burns in 1964. The band’s popularity was severely declining since previous year, cause of the Beatles. Their music was history (the Shads never made it in the U.S. anyway), their gear too. Now British musicians wanted to play American instruments only, preferably semi-acoustic.

Unlike Vox and its many mid-market series Burns focussed on highly evolved quality instruments, partly hand-made, aimed at professional musicians. Those guitars compared with the best America had to offer, also in terms of prices. It could hardly be expected that American musicians would buy such expensive instruments from the U.K. while the Brit colleagues didn’t want them anymore.

Unlike Vox and its product range cleverly mixing highly distinctive shapes and conservative designs, Burns guitars were often a little bit weird but flagship models (Hank Marvin Signature, Jazz Split Sound) were too obviously derived from the Stratocaster, whose popularity was just plummeting. There was still a big demand in the entry level market for Fender copies (from Hagström, Eko, the Japanese, from Vox too) but basically none in the professional sector.

In short, Baldwin had bought at the wrong time the wrong guitar range and wanted to sell them with the wrong people (its sales force had expertise in grand pianos and church organs, not in electric guitars). The venture with its English subsidiary turned out to be a disaster. Burns guitars, fitted with a Baldwin logo and assembled in Baldwin’s Fayetteville, Arkansas, plant, failed miserably on the American market. In 1966 the company tried to cut costs by rationalizing production procedures (a flattened version of the carved scroll headstock that distinguished the H.Marvin model became a standard feature of the whole range), which finished ruining the repute of ex-Burns guitars even in the U.K.

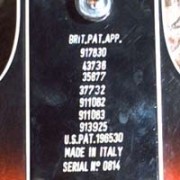

Baldwin soon recognized where the problem was. Since semi-acoustics were in demand, in 1967 Baldwin bought the assets of the Gretsch company to make it a subsidiary and signed an agreement with Crucianelli to provide the intermediate level market with ES-335 style thinline archtops, known as the Baldwin 700 Series. Baldwin even developed a semi of its own, the rare Clyde Edwards model with its handsomely shaped neck joint and asymmetrical neck plate.

Unfortunately the whole guitar market slumped in 1968, especially in the semi-acoustic department. Baldwin ceased shipments from Italy in 1969 and shut down its U.K. operations in 1970. Only survival of Burns technology was the gearbox truss-rod adjustment system, transferred on various Gretsch models. With Gibson and Fender solid bodied designs returning in favour more than ever, Gretsch sales languished in the 70′s and the company was finally closed down in 1981. Baldwin never was lucky in the guitar business.

Italiano

Un venerabile produttore americano di pianoforti e organi – Baldwin di Cincinnati, Ohio – un giorno decise che aveva bisogno di chitarre elettriche per completare la sua gamma. E così comprò nel settembre del 1965 la famosa ditta inglese Burns London, allora sull’orlo della bancarotta.

In USA l’invasione del beat britannico era al suo parossismo e sembrava un’ottima idea proporre chitarre marcate ‘Made in England’. Vox cominciava ad avere un grande successo in America grazie alla sua immagine inglese.

Al contrario di Vox, le chitarre Burns non erano proprio associate al boom del brit-rock del 1963-66. I più noti fra gli utilizzatori erano gli Shadows, passati da Fender a Burns nel 1964. La popolarità del complesso era in rapido declino sin dall’anno prima, forse per colpa dei Beatles. La loro musica apparteneva al passato come i loro strumenti (gli Shadows erano comunque rimasti sconosciuti negli USA). In Albione ormai i musicisti esigevano solo chitarre americane, preferibilmente semi-acustiche.

Contrariamente a Vox e ai suoi tanti modelli di gamma media, Burns era specializzato in chitarre qualitativamente evolutissime, semi-artiginali, per i professionisti. Erano all’altezza della migliore offerta americana, anche in termini di prezzi. Ma non c’era motivo perché i musicisti americani comprassero costosissime chitarre dal Regno Unito proprio quando i loro colleghi britannici non ne volevano più.

Combinando abilmente forme classiche e innovative, le Burns erano spesso un pochino bizzarre ma i cavalli di battaglia (Hank Marvin Signature, Jazz Split Sound) erano troppo evidentemente derivate dalla Strato la cui popolarità era allora in declino. La domanda per le copie delle Fender economiche per principianti (Hagström, Eko, i Giapponesi, e anche Vox) era ancora forte ma praticamente nulla nel settore professionale.

In breve, Baldwin aveva acquistato al momento sbagliato le chitarre sbagliate, che voleva commercializzarle con le persone sbagliate (la forza vendita era esperta in pianoforti da concerto e organi liturgici, non in chitarre elettriche). Il suo tentativo con la filiale inglese si rivelò un disastro. Le chitarre di Burns, ribattezzate con il logo Baldwin e assemblate nell’officina Baldwin di Fayetteville, Arkansas, furono un flop clamoroso negli Stati Uniti. Nel 1966 la compagnia tentò di razionalizzare la produzione per ridurre i costi (una versione più piatta della paletta intagliata a riccio della H.Marvin venne estesa a tutti i modelli), il che portò il colpo di grazia alla fama delle ex-Burns anche in patria.

Baldwin prese coscienza della natura del problema. Poiché il mercato richiedeva semi-acustiche, il gruppo comprò nel 1967 la famosissima Gretsch per farne una filiale, e firmò un accordo con Crucianelli per colmare la fascia intermedia nel mercato delle archtop in stile ES-335, e le denominò Baldwin 700 Series. Baldwin sviluppò anche una semi-acustica tutta sua, il raro modello Clyde Edwards con il suo elegantissimo fissaggio del manico con una placca asimmetrica.

Sfortunatamente nel 1968 il mercato crollò, e in particolare il settore semi-acustico. Nel 1969 vennero fermate le spedizioni dall’Italia. La fabbrica inglese venne chiusa l’anno dopo. L’unica tecnologia della Burns a sopravvivere fu il sistema di regolazione a ingranaggi del truss-rod, trasferito su alcuni modelli Gretsch. Negli anni 70, con le solidbodies di Gibson e Fender tornate di nuovo in voga, Gretsch vide le sue vendite in calo costante e terminò ogni attività nel 1981. Baldwin invece non ebbe mai fortuna nel settore delle chitarre.